A space opera adventure set in a universe controlled and run by Jewish religious authorities. An enforcer is sent to a distant planet where he discovers an android who changes his mind about what is right and wrong.

“Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth; for the first heaven and the first earth passed away, and there is no longer any sea. And I saw the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God.” – The Book of Revelation

1.

The Yom Kippur–class Adjudicator Starship Vey Is Mir left the planet of New Jerusalem at twelve oh five hundred hours Temple Mean Time, en route to the planet Kadesh.

2.

This much we know. This much is logged.

Much of what transpired is guesswork.

3.

“What do you remember?” we ask the man suspended over the sacrificial water of the mikveh. We are deep under the Exilarch’s palace. Shadows flit in the dim red light of the stones set deep into the walls. The air is humid, like a swamp. We think of Capernaum where the green Abominations live. There should be no secrets between us, not here. This is a safe place.

The prisoner is suspended in chains above the murky water. Tiny microscopic organisms swim in that polluted pool, Shayol bacteria, and the prisoner squirms. He knows what they are, what they do. He is afraid.

The prisoner is naked. We examine his body, dispassionately, in the dim red light. His body is a map of old scars, whip and burn marks, gouging and bullets. His body, too, has been modified in past years, in accordance with the forbidden teachings of Rabbi Abulafia, the heretic. This was done by pontifical consent, for did not the Mishna say that the Shabbat may be broken when life is at stake? By which we mean, that this man, who we call Shemesh, was duly blessed by us as an Adjudicator with a license to spoil the Shabbat, by which we mean, well, you follow our drift, we are sure. Certain forbidden technologies were embedded in his flesh, for though he was himself an Abomination nevertheless he performed a holy task in our name.

We are the Exilarch.

We say, “We are most concerned.”

The bound man, suspended upside down over the water where the murderous little creatures of Shayol swim hungrily, makes a rude sound. He uses a rude a word. We are displeased. A scan of his brain pattern reveals disturbing new alignments. We must love him very much, we think, for he is still alive, awaiting our displeasure.

We sigh.

“Child. . .” we say.

“Go to Hell.”

“But we have been there, to that awful planet,” we say, laughing. “And the Treif of Hell-2 will be dealt with as well, in due course. Let us go back, Shemesh, dear Shemesh. Let us go back to when we last saw you.”

“I can tell you nothing,” he says, “that you do not already know.”

We are troubled, but we try not to show it.

“Please,” he says. “Let me down.”

“Tell us about Kadesh.”

His face twists in pain. “It orbits too close to its sun,” he says. “There is no water, no shade. Nothing good ever came of Kadesh.”

“We,” we say, mildly, “were born on Kadesh.”

The man laughs. His laughter is not demented nor tortured, but seems genuine, even pleasant. It upsets us. We lower him down and he stops laughing when the water touches the top of his skull. The tiny little organisms swarm over his scalp and into his ears and his nose and he begins to scream. We lower him further, submerging him in the water, until we choke off the sound.

4.

The man called Shemesh came to the Exilarch’s palace before he left for Kadesh. It is a beautiful place, our palace, we think, less a building and more of a small, bustling town in the heart of New Jerusalem, a complex of offices and temples, housing and stores. It is the very heart of this most holy glorious Intermedium of ours, and the Holy of Holies within is more than 5000 years old, and is a remnant of the old place, of the world we left behind. But you must not know yet of such Mysteries. That place can be visited only by an Exilarch, and we are 3956th of that title.

We received Shemesh in our private offices. Our Massadean guards escorted him into the presence and withdrew. We admired them, these hardy warriors of ours, in their armour with the red Star of David enclosed within a circle. We have many enemies, both within and without. We are ever vigilant: against rebels and Abominations, Obscenities, Treif. . . For beyond the light of the Intermedium, ever present, is the shadow of the Ashmoret Laila and we must guard, always we must guard against incursions.

“Exilarch.”

He performed a perfunctory bow.

“Shemesh. Thank you for coming to see us.”

“I serve at the pleasure of the Exilarch,” he said. He was not a man given to many words, you understand. We hadn’t fashioned him this way. This man, this Shemesh, was an instrument, or so we saw it, of our will.

“A small matter has risen,” we said, smoothly.

“Of course.”

“When was your last mission?”

“Three cycles ago,” he said. “Ashmoret III.”

“Ah, yes,” we said. “You did well there.”

“I was hunted for nights under the seeing moons,” he said, “while the Treif whispered into my mind, a soft and unified whisper of humility and prayer. . .”

“Do you doubt?” we said, sharply. Perhaps we regret it now. Perhaps, like any good tool, he merely needed to be re-sharpened.

“I slaughtered them,” he said, simply; and that satisfied us.

“On the planet Kadesh,” we said, “there is rumour of a holy man. Deep in the caves near the north pole, in the human zone of habitation, he resides. A holy man, and yet he speaks the loshon hora, the evil speech: and he defies the word of the Intermedium.”

“Your word,” he said.

“Our word, yes,” we agreed; a little testily. This is the problem with Adjudicators. They are not. . . whole. They are damaged by definition. And so they tend to mock and question, even their superiors.

Even us.

We tolerate it, on the whole. They have their uses, our tamed assassins, our eyes and ears. We needed Shemesh. The situation on Kadesh was troubling, yet such things are not uncommon, after all. The worlds are filled with false prophets and the speakers of evil tongues. Mostly, a simple procedure heals the body politic. Think of us as surgeons, with a knife.

“We wish for you to travel to Kadesh,” we said. “And ascertain the truth or otherwise of these allegations. Do what you must.”

We waved one of our hands to dismiss him, but he remained put.

“You wish me to spoil the Shabbat?” he said.

“Spoil,” we said, “with extreme unction.”

5.

The Yom Kippur–class Adjudicator Starship Vey Is Mir left the planet of New Jerusalem at twelve oh five hundred hours Temple Mean Time, en route to the planet Kadesh. This much we know. Much of what transpired is guesswork.

She was a relic of the Second Maccabean War. A swift old war bird, she was equipped with a Smolin Drive, which was engaged as soon as it passed the heliosphere. It attained light speed and shot into the dark of galactic space.

Light, we understand, does not travel at quite the same speed here as it did in the place we left behind. The journey between planets is swift, here. It took the ship 45 hours to reach Kadesh orbit. What Shemesh did in that time, we do not know. We hope he prayed – but we rather doubted it.

Perhaps he slept. Perhaps he studied the dossier of the man he had to kill. We knew little of this preacher, but that he called himself Ishmael. A choice of a name well fitting a renegade. We ourselves, before we became Exilarch, were born in Akalton, the second largest of the planet’s settlements, to which Shemesh himself was headed. Our childhood was happy, we remember. We loved the desert, the dry heat. New Jerusalem’s a colder place, and we have never stopped entirely marvelling at rain.

Rain! Water that falls down from the sky! In Akalton our mother was a trader in water futures. Our father sold breeds of Zikit, the hardy lizard-like creatures native to that planet, on which we rode and hunted and transported our goods. One feels very close to God, on Kadesh. Many of our predecessors came from that planet, but equally many false prophets emerge there, then and still, and we must always watch for trouble from that region. Our Massadean forces keep a permanent base on Kadesh, but in truth, there is little they can truly do on that harsh world, where communities are ever mobile, and where the ancient polar caves provide a shelter to any manner of galactic outlaw. . .

But this is not our story, this is the recording of minutes concerning the expedition of Shemesh, who is suspended over the sacrificial water, back in the air, breathing, as our appendages probe the forbidden interface that lies in the base of his brain, painfully extracting information.

6.

The Testament According To Shemesh, Part I

The ship began to slow as we entered the Kadesh-Barnea system. Beside the habitable planet, there are two gas giants in the outer system, orbited by many moons, and between them and the planet Kadesh, nearby space is filled with habitats of all kinds. On Kadesh they grow the Artemisia judaica, and it is the source of much of their trade. A non-native plant, it came from that place we left behind, yet changed in the crossing. The breeds they grow on Kadesh are valued as medicine throughout the Intermedium and even in the forbidden worlds of the Ashmoret Laila on the rim; and though Kadesh is a harsh world, it is also a rich one.

This explained, then, the profusion of habitats throughout the system, and transport ships swarmed in nearby space. Around the planet itself, in orbit, I observed numerous small satellites, way stations, and docking bays. The Vey Is Mir, however, is adapted for planetary landing, and in short order I arrived in Akalton City, where my Adjudicator badge let me pass through quarantine.

It is a strange and melancholy place. . . the reddish-brown buildings looked as though they were built of the desert itself. The world smelled of dried thyme, cinnamon, and salt, for the area around the settlement was home to many salt mines, and it was this commodity, rather than the Artemisia, that was most on display as I walked through the quiet streets. Though buildings seldom came higher than two stories, nevertheless the streets, having been built close together, formed a narrow maze that felt oppressive, at times dangerous. The sun had set, and the first stars came out. It is always a shock, the first time one encounters a new sky, no matter how often one visits new planets. It provokes the strongest sense of dislocation, almost of loss.

Wonder, too, though the sense of wonder soon fades, and one is left mostly with unease at the alien stars.

Since the stars came out, the streets filled with people heading to temple, though many stood and prayed outside their shops or homes for Ma’ariv. The people of Kadesh wore long, flowing robes, their faces covered against the sand that always blew through the air. Many wore elaborate air filtration systems over their faces, and thus robed and masked they passed through the narrow streets of that town.

. . . I had the sense of being watched.

I picked my way carefully. The instruments deep within my skull analysed the Kadeshean’s bodies. Many carried kukri knives, long and curved and deadly. Others carried dart guns, salt revolvers, even Vipera kadesheana, those semi-domesticated, poisonous snakes which are used by the natives in deadly close combat.

The pension I was headed to lay at the edge of the town, where Akalton ends and the desert begins. It was as I was passing the gladiatorial amphitheatre that the first attack happened. . .

The amphitheatre stood behind mud-coloured walls. Though the law forbids such games, the populace, being simple folk, love them to the detriment of their duties, and so it was deemed by some former Exilarch that they should be, if not legalised, than at least managed and, naturally, taxed. Now it provided easy entertainment to otherwise pious citizens, who flocked to view bloodied spectacles of human gladiators fighting captured Treif. The area around the arena thronged, even at that hour, with disreputable characters, many armed, and so when the first blow came, I was prepared—

I fell down and swept the assailant’s feet from under him and he fell. My knife was already in my hand and it found his heart before he had time to move. There were three more of them converging on me, two brutes who with their size could only have been Goliaths, and a small, nasty-looking angel with the mark of Cain on his brow.

The angel took me by surprise. The angels, by which we mean messengers, emanate from the holy see in New Jerusalem. They are augmented, chosen of all the worlds for being the brightest and the most studious and pure. When still young, they are taken to the facilities deep beneath the holy see, where Talmudic engineers refashion them into beings both less, and more, than human. There is a bitter argument recorded in the Tractate Nephilim of 3812, between Rabbi Mohandes and Rabbi Gilman of the Gilmanites of Hastur-3 (of whom it was said that he always walked in shadow), as to the ascendancy of angelic souls at the time of the Final Resurrection. For Rabbi Mohandes said, Lo, that they may not arise as they have never truly lived as men. And Rabbi Gilman said, On the contrary, for they are more than men, and so they will be first to be awakened when the final shofar is blown by the Archangel Gabriel, for it will be they who will usher the new souls into the afterlife.

But I had bigger problems than what the ancient sages thought on the issue of angels, as the small, nasty one was coming at me with a knife. It was a horrible little blade, made of bio-hazardous nanowire filaments woven together: its very whisper through the air could kill. I plugged one of the two Goliaths with a high-bore bullet to the brain and it collapsed with a grunt. I rolled backwards as the angel came at me, kicking as his arm descended. He shrieked with fury and bared small, even white teeth in a rictus of hate. In all my time serving I had only met one other angel with the mark of Cain upon its face: its protocols had been corrupted by an Ashmedai-level hostile intrusion from the Ashmoret Laila.

How this one came to be here I couldn’t even begin to speculate. The second Goliath smashed a fist into me, sending me flying over the heads of the crowd until I crashed into a moneylender’s stall. As it came thudding after me the crowd dispersed as fast as they could. From beyond the walls of the arena came the frenzied shouts of spectators as some unlucky Treif was no doubt gored. I myself had no taste for violent spectacle.

I rose to my feet. The angel came at me more slowly, then. Its eyes glowed with ultraviolet light and it rose above the ground, manipulating magnetic fields as it flew. The Goliath, with a smirk of triumph, blocked my escape.

I was trapped.

The angel hovered in the air above me. He looked down on me, a heavenly castrato with the eyes of Ashmedai itself.

“Three times,” he intoned, in his high, youthful voice, “three times shall you be besieged, assassin, and three times you shall be tested.”

Then he smiled, a wicked smile, and the knife grew in his hand and became a shining sword. “Or just once, if you’re lucky.”

And he dove at me.

I assumed the Yona Wallach defence and as the sword swung a second time I counterattacked with an Alterman combined with a two-strike Adaf move that saw the angel fly back. As the Goliath at my back moved to contain me I twisted my body round him until I was at his back, pressing against it, and then I pushed. He screamed as my flesh burned into his own and I burrowed into his body, dislodging vertebrae and kidneys, thighbones and intestines. I made the body move, blindly groping for the angel. I heard the whisper of the blade as it connected with neck muscles and severed them. The Goliath’s head fell to the ground, bounced twice, and lay still. The angel screamed with rage. I reached for him with the giant’s arms. I was safe inside the tank-like body. Then I heard gunfire, as the local Massadean peace-keeping force arrived to save the day. The angel shrieked again, then departed. I disengaged myself slowly and painfully from the Goliath’s corpse and watched it as it crashed to the ground. I was covered in gore, dripping in slime, and in a very bad mood. I hadn’t even been on the planet one full rotation. The Massadeans had their guns trained on me and I sighed.

“My name,” I said, “is Shemesh. I am a full level Adjudicator on a mission from the holy see. . .”

As you can imagine, it took me a while to convince them.

7.

The Testament According To Shemesh, Part II

I spent the night in a cell in the Massadean barracks.

The Massada mercenaries always put me in mind of lethal mushrooms. They are, on the whole, small and wiry, and they move with a deadly sort of precision that makes even a trained operative, even a high-level Adjudicator, uneasy. In all the worlds of the Intermedium there is no one more dangerous than a Massadean. They live in barracks from childhood and train in every form of martial art and every weapon ever invented, and on their bar mitzvah they get dropped on a rim planet, a group of them, and are expected to survive a month among Amalek-level Treif. Less than half of them usually make it off-world by the time it is over and by then, they have shed more blood than the prophet Elijah when he was faced with the priests of Ba’al.

. . . In the night, somebody tried to poison me.

Three times shall you be besieged, assassin, and three times you shall be tested, the angel had said.

I woke up with the dripping of liquid, close to my ear. I looked up, saw two yellow eyes stare at me from the ceiling. She was dressed all in black, and it took me a moment to realise just how inhuman she was, how her limbs were like a spider’s, and how the sack of bilious material that hung from her midsection was a sting, and it was pointed down at me.

. . . I assumed the defensive Tchernichovsky position but there was nowhere to run. It is good for close quarter defence and attack but the creature above me, this Abomination, merely hissed. The dripping poison, I noticed with horror, had set the bedding alight. Flames began to billow and the thick smoke made it hard to breathe. I began to call for help. The creature hissed again, firing poison at me from her sting. I ducked and it hit the bars and melted them with a hiss. Then the Massadean guards were in the cell, and opening fire, and the Abomination was shredded into black ichor.

Hands dragged me out as poison exploded all over the walls. It was nasty stuff – I had not run into a Treif species of this kind before, had no idea where in the rim it could have come from. How it could breach Massadean security, I had no idea either. Someone – more than someone – would pay with their head for this.

I wasn’t happy about the way events were turning. After having a shouted argument with the Massadean colonel in charge of the base, I was finally let go. From there I made my way through empty, half-deserted streets to the edge of town and my original destination. The night had turned cold, and the alien stars shone down unobstructed. At that moment I missed New Jerusalem, its eternal lights which mask the view of the night sky. There were too many stars in the sky and they all felt like eyes, watching.

I made my way to the pension, retrieved the pack that was waiting for me, as well as my escort, a sleepy youth from one of the desert tribes. Two of the lizard creatures called Zikit were waiting for us in the yard. We mounted them, and by dawn we had left the city of Akalton far behind.

8.

Our glittering eyes examine the bound prisoner. This was our servant, we marvel, this was the man we had sent out on our behalf. Yet something had happened to him, on our home planet. Something had changed him, had tested his loyalty to us.

We. . . are. . . Exilarch!

The fate of this entire universe and the chosen people within it rests with us. It has not always been thus, but we are they who were called the Resh Galuta: the ultimate authority in our exile.

“Tell us,” we whisper. “Tell us the truth. Why do you deny it to us?”

Shemesh screams. The screams last a long while. Our manipulating digits caress the many wounds inflicted upon his person, both old ones, and new. We poke and we twist.

“Tell us!”

The man, this Adjudicator, hangs there, broken, defeated.

“Kill me,” he begs.

But that will not do; not do at all. We scan and we sieve through this man’s mind, his various augmentations, we taste of his blood and we sample his tissues. We must understand. We absorb him unto ourselves. Things clear, gradually. A picture forms. Clouded at first, then more sharply defined. We know many things. We know that the second attacker, for instance, was a Lilith, a Treif species we had long thought extinct; servants of the Ashmoret Laila, they had terrorised countless planets in the Great Amalek Rebellion of 2500 A.E., swooping in the night, devouring the flesh and bones of all who stood in their way. . . they were poison, Abominations, Treif. . . but we had swooped down on the enemy with swords of flame, with Av-9 starships capable of mass destruction, and the enemy was beaten away, to the rim, and the Lilith were destroyed to the last. . . or so we thought.

We had been wrong. This was disturbing. We magnify the image, construct a memory.

We observe.

9.

The two men ride in the shadow of tall rising cliffs. The canyon floor is yellowish-red sand. For a moment we are filled with a longing for home. . .

The lizards move slowly, slowly in the heat. The men seem half-asleep in their saddles. They have been riding a long time, we think.

We zoom in on them. Lichen grows in cracks in the stone walls of the canyon. There is Shemesh, and there is his companion, whose name is Shlem. He is little more than a boy, really. We know his kind. A desert rat, of the tribes who throng this polar region, paying only lip service to the one true faith. They are a wilful peoples, stubborn, independent, unruly. The boy belongs to a tribe we have had transactions with. They are loyal, for a price. In the polar caves, we know, reside insurgents, escaped Treif, all manners of lawless man and beast. But we cannot police them, we can only contain. As long as they remain unseen, we pretend they are not there.

The boy, all this meanwhile, is speaking. He speaks in a neverending stream, while the Adjudicator’s head nods, less in agreement than with the movement of the beast on which he rides. We tune in, to try and see if it has any relevance to what we need to know:

“. . . in Tel Asher. She said she’d wait but it’s been two cycles and our caravans have not yet crossed again. Do you think it would be wrong to. . .? But you asked about the prophet, this Ishmael. Few have seen him, but word spreads. People come to see him, he speaks from the caves, and they come back transformed, speaking the word of rebellion. But you asked about Treif, yes, many pass through here, seeking refuge, in the caves, they say, are entire species thought lost. They are not of the chosen, and they are not people, and yet I met one, once, near human in shape, and comely, though there is a distinct sense of repulsion, too, of alienation emanating from them, and yet it spoke, in the common tongue, and she – it, it spoke well.”

The boy blushes. The man, Shemesh, stirs. “And you, do you believe the word of this Ishmael, too?”

“Do you mean, am I leading you to your doom?”

“The thought had crossed my mind.”

“I am loyal.”

“But you have heard him speak?”

The boy shakes his head; and yet the question seems to have struck him strangely mute. He stares elsewhere, at the shadows, and says nothing more. We zoom back, until they shrink into two tiny dots, crawling along the immense wall of the cliff. We track their progress. Night falls. The sun rises. It becomes hard to follow, where they go. There are odd phenomena in that polar region, magnetic interference, and though this is, we think, our agent’s recollection, there are odd gaps in it, and we find that we cannot trace the route he’d taken. . .

They reach, at last, a wall, and stop. The beasts look nervous. The two dismount. The boy does something, we cannot tell exactly what. It’s galling! And we realise someone has interfered with this memory – though surely that should be impossible.

Something changes. Something opens. Like an eye in the rock. Like the spiral of a snail. Like the head of a flower.

An entrance – cunningly disguised.

Shemesh looks at the boy. He speaks, but what he says, we cannot tell. The boy nods—

And a figure rises in the air above them, a sword of flame held in its hands. Shemesh turns, draws a gun, fires. The sword swings. The boy raises his arm. His face registers shock. The angel’s face is beatific. We know him, he was one of ours, we thought him lost long ago, on Ashmoret I, our angelic child, the sword whispers through the air and slices through the boy’s neck and severs his head from his shoulders.

Shemesh fires, again and again. His gun is a silver Birobidzhan, an item of forbidden technology, with Av-9 destructive capabilities otherwise confined to warships. How Shemesh ever got hold of one, we do not know. One bullet grazes the angel’s wing and he screams, though we get no sound. The sword of flame flashes forth and it misses Shemesh’s head and cuts through the canyon’s rock wall as though it were nothing. Then Shemesh fires once more and the bullet catches the angel in the chest and it falls, wounded, to the sand. Shemesh goes and stands over him, over our child, our angel. He points the Birobidzhan at the angel’s head.

They speak, we think. But we cannot tell what they say.

Shemesh points the gun at the angel’s head.

He pulls the trigger.

10.

The Testament According To Shemesh, Part III

I fled through the tunnels.

Three times, the angel had warned me, and three times they’d failed. I began to think that this was intended, but I did not understand the needless sacrifice. It was cooler in the tunnels. They were dug into reddish stone, and seams of a gleaming, mercurial metal ran through the walls, providing faint illumination. At odd intervals, alcoves had been dug into the side of the tunnels. As the tunnels continued to widen around them, I began to discern the curious inhabitants of the polar caves.

They were, mostly, of the chosen. Who they were I did not know. They stared at me from their alcoves, young, old, all those who had turned their backs on the outside world. Amongst their number I began to discern the Treif: alien species, indigenous to this universe, which never knew the Creator. They were creatures who had never received the Torah.

None approached me. None challenged me. I kept walking, deeper and deeper into the caves.

For caves they were, I realised. The tunnels themselves were mere blood vessels in what was an unimaginably huge subterranean structure. I passed through enormous caverns where the ceiling glittered with precious stones and seams of minerals high above, and I encountered underground rivers where, along the banks, there stood permanent villages, solid constructions in wood and metal.

I saw entire stone cities dug into the walls.

I saw glimmering vistas and shanty towns, crystal lakes, and red stone cemeteries where rows of graves went on and on until they disappeared deep within the recesses of the rock. I began to realise we had been wrong, grievously wrong to dismiss this place, to put it out of our thoughts. This was not an isolated, easily contained outpost of lawlessness – but rather, it was a major base of operations for the Ashmoret Laila.

None of the Treif approached me. I saw the group-mind molluscs of Ashmoret III; the life force creatures of the Arpad system, leech-creatures of pure energy humming as their force fields hung in the air; the little termite things of Mazikeen-5; in one vast lake I saw a behemoth fighting, or perhaps mating with, a Leviathan; on and on they went, these creatures of the Ashmoret Laila, yet none attacked me, for all that I was helpless in their presence. Instead, they moved out of my way, and watched me, almost respectfully, as I passed.

But where was I going? It began to occur to me that I had always been on this path, and that my route was pre-determined before ever I had left New Jerusalem. An unseen hand moved me like a puppet along this route, and I felt the pull of my invisible quarry lead me along, through this vast and subterranean world under the pole.

. . . at last I came to a temperate valley, smelling of vegetation.

A brook bisected this cavern and disappeared into the wall. By the side of the rock there was a small, makeshift hut, a little like a Passover sukkah. It is the holiday we celebrate for passing from the old universe to this one, so long ago, and the presence of the sukkah was incongruous in these surroundings. Here, amidst the hidden denizens of the Ashmoret Laila, our Passover was no cause for celebration, but for mourning; for what we call Passover, they inexplicably call Invasion.

I approached the hut, which is when I saw him. He sat on a rock, by the stream, and looked into the water. At the sound of my approach he turned, and smiled. I had the Birobidzhan already in my hand and pointing at him. I looked him over.

“So you’re the prophet,” I said.

“. . . call me Ishmael.”

I stared. He was not what I had expected. . .

“I have been waiting for you, for someone like you. I have been waiting a long time.”

I stared.

“Well? Are you going to shoot me?” he said.

11.

There is something wrong with the memory, something profoundly wrong. The prisoner twists and turns on the chains above the mikveh. We try to tune the image, to sharpen it. Our tentacles grate into his skin. We cause him a great deal of pain, we think. His organic form is too delicate to withstand such pressures. His body is coming apart at the seams. Yet we keep him alive. We need him, what he carries.

We magnify. We see.

Though it has human form, it is no human being.

An Abomination.

The picture grows fuzzy, then clear. We can hear their voices now, tinny in our ears.

Shemesh: “You’re a robot?”

Ishmael: “Not. . . exactly.”

He looks at Shemesh, and smiles; and we have the sudden and awful feeling that he – it – is looking at us. It has silver skin and a humanoid shape, an expressive mouth, sharp, twinkling eyes. We had thought its kind extinct; like the rest.

Shemesh: “Then what are you?”

Ishmael: “It was Rabbi Abulafia, in the first millennium A.E., who posited a heresy.”

Shemesh: “Yes?”

“Things were different in that time. The worlds were wilder, the chosen were fewer, the laws were less rigid. There was an Exilarch, but back then it was just a person with a title, not the. . . thing it has since become. At that time there were still the indigenous worlds, of what you, in your ignorance, call the Ashmoret Laila, those of the night. They were not yet confined to the rim, pushed from their home worlds, made to hide in places such as this, in the forgotten nooks and crannies of the universe.”

Shemesh: “Thank you for that history lesson.”

Ishmael: “Which you need. This history has been erased.”

Shemesh: “It is a lie.”

Ishmael: “At that time, relations were different. There was trade, there were even friendships. And then Rabbi Abulafia posited the heresy for which he would be condemned in generations to come. For he suggested that we were not, after all, Treif. That though we were different life forms, we were still God’s chosen, too, just as you were.”

Shemesh: “I was sent to kill you.”

Ishmael smiles. Can a robot smile? We wonder, uneasily. We try to focus on him – it. He seems so at peace.

Shemesh: “What are you?”

Ishmael: “Let me show you.”

He reaches for his chest, and opens it.

Inside we see a glistening, organic thing. A complex network of tubing and blood. We think of the mind-molluscs of Ashmoret III. We note Shemesh’s eyes widen.

They speak to him, we realise. Telepathically. These Abominations, these creatures we would have die a thousand deaths.

Treif! We scream. Prohibited!

We will Shemesh to shoot. To press the trigger! Kill it, kill them all, as you did all the others, boy!

Yet Shemesh stands frozen.

12.

The Testament According To Shemesh, Part IV

The creatures had me then. Once more I was transported to my last mission, hunted under the moons of Ashmoret III; for endless nights I ran through the low-lying, humid swamps, seeking shelter in caves and hidden alcoves, as the Treif spoke into my mind, whispering words of love and forgiveness and sorrow, and saying that this was all folly. Endlessly I ran, firing, and they died, but more and more came. Then the Vey Is Mir arrived, to rescue me off-planet, but this was not real, I knew, it had the logic of dream. It flew in the speed of light, and I could see the whole universe spread out before me, in the great galactic dark: New Jerusalem at its heart, emanating forth its influence and power. One by one I counted them, Masada, Shayol, Golgotha, Macabea, the twin system of Kadesh-Barnea, Capernaum where the green Abominations lived, Migdal and Amalek and Endor, Sodom, Gomorrah: the worlds of the Ashmoret Laila on the rim, dark, dark against the light of the chosen. Then it all receded, farther and farther away and back in time, back through the centuries and the millennia, contracting to a single point of light: a window.

And a new thought, so alien I did not understand the words.

Deep under the Weizmann Institute in Rehovot, just south of Tel Aviv. Deep down underground, in the secret caverns only those with the highest security clearances even know about, a test is in progress. The technicians run cables to the diamond-shaped device and, behind their monitors, the scientists twitch nervously, checking and rechecking readings and projections.

It is nearly time.

A hush slowly settles over those assembled. It is accentuated by the low hum of the computers, the thrum of the backup generators, the hiss of water, the cough of a solitary smoker, the shuffling feet of the posted soldiers.

When it happens, it happens all at once.

The diamond-shaped device explodes in shards of cold light, like the screen before a movie projector. It shudders and then stabilises. The light fades.

It’s black. They all crane over to see. It is dark, and immense, and then one pinprick of light and then another begin to glow in the black velvety darkness, and someone – it is never clear, afterwards, who – lets out a loud breath of wonder.

“My God,” they say. “It’s full of—!”

“Now do you see?” Ishmael said; but I saw nothing, I was blind, I was afraid.

This is the last will and testament of the Adjudicator, Shemesh. The creatures released their hold on me. My finger tightened on the trigger of the gun. Ishmael watched me. And I remembered what his name meant, at that moment.

“God will hear”, in the old tongue, of the place we left behind.

I pulled the trigger.

13.

No! we howl. No!

We see it. We see it now. Too late. Our Adjudicator’s mutilated corpse hangs from the chains that bind him. The tiny, blind micro-organisms of Shayol crawl over his skin, in his blood. He is devoured. We see it, we see it now. Too late.

The soft explosion.

The robot, falling back. The spongy bio-matter in its chest, exploding. The silent, watching Treif.

Shemesh, looking down. A bemused expression on his face. The spores, we want to shout, the spores! He turns. He leaves. And all over Low Kadesh Orbit, satellites come alive and begin transmitting.

No. . . we whisper. Shemesh hangs dead from his chains, yet his eyes open, his mouth moves. He speaks to us, in words of compassion and sorrow, speaking the ancient heresy of Abulafia, saying that we are all the same. And we think of the old world, the one we had left behind, how in antiquity they’d capture our agents and send them back to us, booby-trapped.

Such an elaborate seduction. It must have taken years to plan. The robot, planted on Kadesh. The word, trickling out. All for this moment, all in wait for the Adjudicator to come.

To come, and do his job, and return to his nest, return to the holy see, return to us.

No, no! we moan. Shemesh is Treif, he is contaminated, his blood drips into the mikveh, his eyes stare out at us. We try to flee. Too late. It’s in us.

We shake our tentacles. We flee to our Sanctum.

We. . . are. . . Exilarch!

Yet our shout of defiance comes weak. We flee to our window, here, in the old dispensation, with an alien people clutching their gods. We look out over New Jerusalem, over the Temple, and we look up, at the stars, all those stars. Our protocols are being compromised, we are infected with that which is not pure, unchosen. We are become Treif.

We look up at the stars. We look at the horizon. We feel a great peace descend on us. No, no. We must fight it. On the edge of the horizon, light streaks. Dawn breaks, and the first tendrils of sunlight begin to chase away the dark.

The sun.

The word is “Shemesh”, in the old tongue.

We stare, spellbound, as day breaks; and we look upon at last and see the new Jerusalem.

“The Old Dispensation” copyright © 2017 by Lavie Tidhar

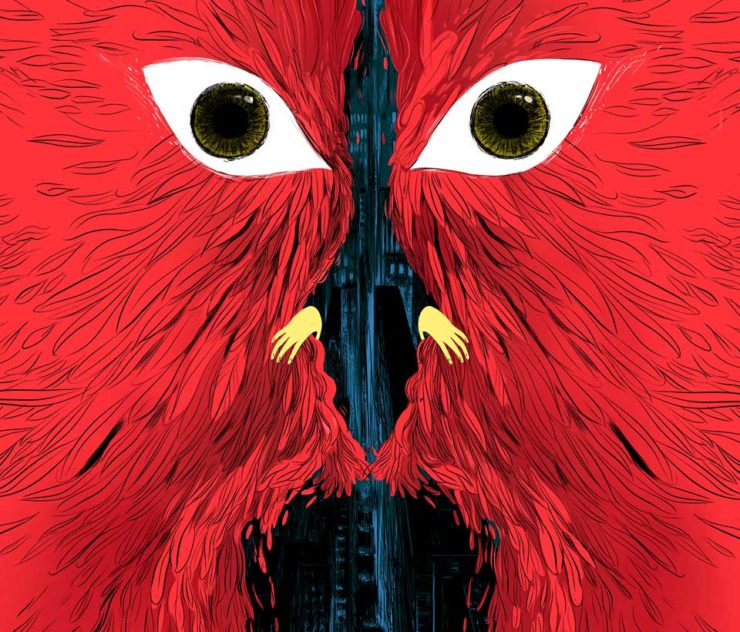

Art copyright © 2017 by Wesley Allsbrook